The race to save our online lives from a digital dark age

We’re making more data than ever. What can—and should—we save for future generations? And will they be able to understand it?

There is a photo of my daughter that I love. She is sitting, smiling, in our old back garden, chubby hands grabbing at the cool grass. It was taken in 2013, when she was almost one, on an aging Samsung digital camera. I originally stored it on a laptop before transferring it to a chunky external hard drive.

A few years later, I uploaded it to Google Photos. When I search for the word ”grass,” Google’s algorithm pulls it up. It always makes me smile.

I pay Google £1.79 a month to keep my memories safe. That’s a lot of trust I’m putting in a company that’s existed for only 26 years. But the hassle it removes seems worth it. There’s just so much stuff nowadays. The admin required to keep it updated and stored safely is just too onerous.

My parents didn’t have this problem. They took occasional photos of me on a film camera and periodically printed them out on paper and put them in a photo album. These pictures are still viewable now, 40-odd years later, on faded yellowing photo paper—a few frames per year.

Many of my memories from the following decades are also fixed on paper. The letters I received from my friends when traveling abroad in my 20s were handwritten on lined paper. I still have them crammed in a shoebox, an amusing but relatively small archive of an offline time.

We no longer have such space limitations. My iPhone takes thousands of photos a year. Our Instagram and TikTok feeds are constantly updated. We collectively send billions of WhatsApp messages and texts and emails and tweets.

But while all this data is plentiful, it’s also more ephemeral. One day in the maybe-not-so-distant future, YouTube won’t exist and its videos may be lost forever. Facebook—and your uncle’s holiday posts—will vanish. There is precedent for this. MySpace, the first largish-scale social network, deleted every photo, video, and audio file uploaded to it before 2016, seemingly inadvertently. Entire tranches of Usenet newsgroups, home to some of the internet’s earliest conversations, have gone offline forever and vanished from history. And in June this year, more than 20 years of music journalism disappeared when the MTV News archives were taken offline.

For many archivists, alarm bells are ringing. Across the world, they are scraping up defunct websites or at-risk data collections to save as much of our digital lives as possible. Others are working on ways to store that data in formats that will last hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of years.

The endeavor raises complex questions. What is important to us? How and why do we decide what to keep—and what do we let go?

And how will future generations make sense of what we’re able to save?

“Welcome to the challenge of every historian, archaeologist, novelist,” says Genevieve Bell, a cultural anthropologist. “How do you make sense of what’s left? And then how do you avoid reading it through the lens of the now?”

Last-chance saloon

There is more stuff being created now than at any time in history. At Google’s I/O conference this year, the firm’s CEO, Sundar Pichai, said that 6 billion photos and videos are uploaded to Google Photos every day. More than 40 million WhatsApp messages are sent every minute.

Even with so much more of it, though, our data is more fragile than ever. Books could burn in a freak library fire, but data is much easier to wipe forever. We’ve seen it happen—not only in incidents like the accidental deletion of MySpace data but also, sometimes, with intent.

In 2009, Yahoo announced it was going to pull the plug on the web-hosting platform GeoCities, putting millions of carefully created web pages on the chopping block. While most of these pages might seem inconsequential—GeoCities was famous for its amateurish, early-web aesthetic and its pages dedicated to various collections, obsessions, or fandoms—they represented an early chapter of the web, and one that was about to be lost forever.

And it would have been, if a ragtag group of volunteer archivists led by Jason Scott hadn’t stepped in.

“We sprang into action, and part of the fury and confusion of the time was we were going from downloading a handful of interesting sites to suddenly taking on an anchoring website of the early web,” Scott recalls.

His group, called Archive Team, quickly mobilized and downloaded as many GeoCities pages as possible before it closed for good. He and the team ended up being able to save most of the site, archiving millions of pages between April and October 2009. He estimates that they managed to download and store around a terabyte, but he notes that the size of GeoCities waxed and waned and was around nine terabytes at its peak. Much was likely gone for good. “It contained 100% user-generated works, folk art, and honest examples of human beings writing information and histories that were nowhere else,” he says.

Known for his top hat and cyberpunk-infused sense of style, Scott has made it his life’s mission to help save parts of the web that are at risk of being lost. “It is becoming more understood that archives, archiving, and preservation are a choice, a duty, and not something that just happens like the tides,” he says.

Scott now works as “free-range archivist and software curator” with the Internet Archive, an online library started in 1996 by the internet pioneer Brewster Kahle to save and store information that would otherwise be lost.

As a society, we’re creating so much new stuff that we must always delete more things than we did the year before.

Over the past two decades, the Internet Archive has amassed a gigantic library of material scraped from around the web, including that GeoCities content. It doesn’t just save purely digital artifacts, either; it also has a vast collection of digitized books that it has scanned and rescued. Since it began, the Internet Archive has collected more than 145 petabytes of data, including more than 95 million public media files such as movies, images, and texts. It has managed to save almost half a million MTV news pages.

Its Wayback Machine, which lets users rewind to see how certain websites looked at any point in time, has more than 800 billion web pages stored and captures a further 650 million each day. It also records and stores TV channels from around the world and even saves TikToks and YouTube videos. They are all stored across multiple data centers that the Internet Archive owns itself.

It’s a Sisyphean task. As a society, we’re creating so much new stuff that we must always delete more things than we did the year before, says Jack Cushman, director at Harvard’s Library Innovation Lab, where he helps libraries and technologists learn from one another. We “have to figure out what gets saved and what doesn’t,” he says. “And how do we decide?”

Archivists have to make such decisions constantly. Which TikToks should we save for posterity, for example?

We shouldn’t try too hard to imagine what future historians would find interesting about us, says Niels Brügger, an internet researcher at Aarhus University in Denmark. “We cannot imagine what historians in 30 years’ time would like to study about today, because we don’t have a clue,” he says. “So we shouldn’t try to anticipate and sort of constrain the possible questions that future historians would ask.”

Instead, Brügger says, we should just save as much stuff as possible and let them figure it out later. “As a historian, I would definitely go for: Get it all, and then historians will find out what the hell they’re going to do with it,” he says.

At the Internet Archive, it’s the stuff most at risk of being lost that gets prioritized, says Jefferson Bailey, who works there helping develop archiving software for libraries and institutions. “Material that is ephemeral or at risk or has not yet been digitized and therefore is more easily destroyed, because it’s in analog or print format—those do get priority,” he says.

People can request that pages be archived. Libraries and institutions also make nominations. And the staff sorts out the rest. Across open social media like TikTok and YouTube, archive teams at libraries around the world select certain accounts, copy what they want to save, and share those copies with the Internet Archive. It could be snapshots of what was trending each day, as well as tweets or videos from accounts run by notable individuals such as the US president.

The process can’t capture everything, but it offers a pretty good slice of what has preoccupied us in the early decades of the 21st century. While historical records have typically relied upon the private letters and belongings of society’s richest, an archive process that scrapes tweets is always going to be a bit more egalitarian.

“You can get a very interesting and diverse snapshot of our cultural moments of the last 30, 40 years,” says Bailey. “That is very different from what a traditional archive looked like 100 years ago.”

As citizens, we could also help future historians. Brügger suggests people could make “data donations” of their personal correspondence to archives. “One week per year, invite everyone to donate the emails from that week,” he says. “If you had these time slices of email correspondence from thousands of people, year by year, that would be really great.”

Scott imagines future historians eventually using AI to query these archives to gain a unique insight into how we lived. “You’ll be able to ask a machine: ‘Could you show me images of people enjoying themselves at amusement parks with their families from the ’60s?’ and it will go, ‘Here you go,’” he says. “The work we did up to here was done in faith that something like this might exist.”

The past guides the future

Human knowledge doesn’t always disappear with a dramatic flourish like GeoCities; sometimes it is erased gradually. You don’t know something’s gone until you go back to check it. One example of this is “link rot,” where hyperlinks on the web no longer direct you to the right target, leaving you with broken pages and dead ends. A Pew Research Center study from May 2024 found that 23% of web pages that were around in 2013 are no longer accessible.

It’s not just web links that die without constant curation and care. Unlike paper, the formats that now store most of our data require certain software or hardware to run. And these tools can become obsolete quickly. Many of our files can no longer be read because the applications that read them are gone or the data has become corrupted, for example.

One way to mitigate this problem is to transfer important data to the latest medium on a regular basis, before the programs required to read it are lost forever. At the Internet Archive and other libraries, the way information is stored is refreshed every few years. But for data that is not being actively looked after, it may be only a few years before the hardware required to access it is no longer available. Think about once ubiquitous storage mediums like Zip drives or CompactFlash.

Some researchers are looking into ways to make sure we can always access old digital formats, even if the kit required to read them has become a museum piece. The Olive project, run by Mahadev Satyanarayanan at Carnegie Mellon University, aims to make it possible for anyone to use any application, however old, “with just a click.” His team has been working since 2012 to create a huge, decentralized network that supports “virtual machines”—emulators for old or defunct operating systems and all the software that they run.

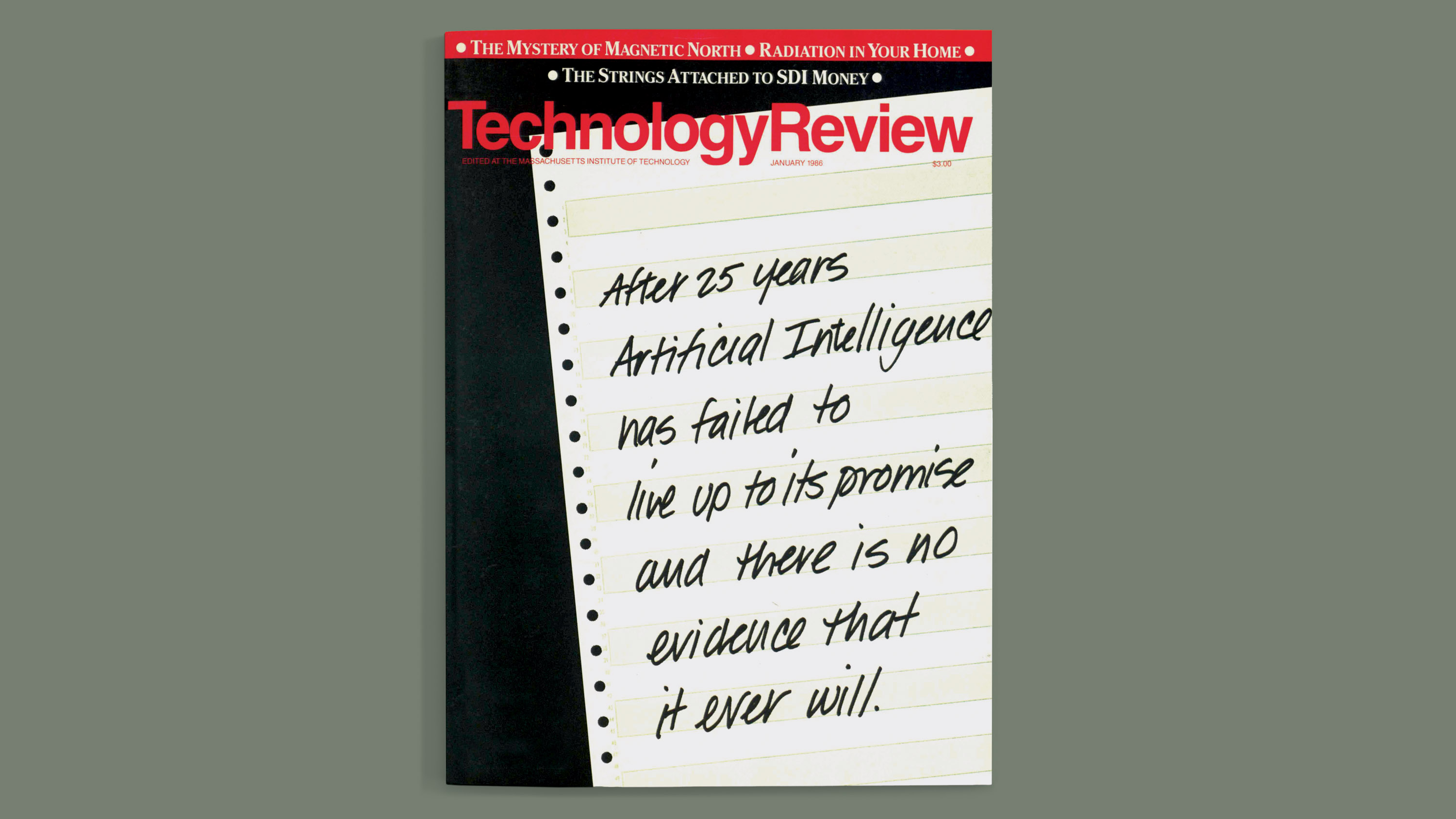

Keeping old data alive like this is a way to protect against what the computer scientist Danny Hillis once dubbed the “digital dark age,” a nod to the early medieval period when a lack of written material left future historians little to go on.

Hillis, an MIT alum who pioneered parallel computing, thinks the rapid technological upheaval of our time will leave much of what we’re living through a mystery to scholars.

“As I get older, I keep thinking, how can I be a good ancestor?”

Vint Cerf, one of the internet’s founders

“When people look back at this period, they’ll say, ‘Oh, well, you know, here was this sort of incomprehensibly fast technological change, and a lot of history got lost during that change,” he says.

Hillis was one of the founders (along with Brian Eno and Stewart Brand) of the Long Now Foundation, a San Francisco–based organization that is known for its eye-catching art/science projects such as the Clock of the Long Now, a Jeff Bezos–funded gigantic mechanical clock currently under construction in a mountain in West Texas that is designed to keep accurate time for 10,000 years. It also created the Rosetta Disc, a circle of nickel that has been etched at microscopic scale with documentation for around 1,500 of the world’s languages. In February, a copy of the disc touched down on the moon aboard the Odysseus lander. Part of the Long Now’s focus is to help people think about how we protect our history for future generations. It’s not just about making life easier for historians. It’s about helping us be “better ancestors,” according to the organization’s mission statement.

It’s a sentiment that chimes with Vint Cerf, one of the internet’s founders. “As I get older, I keep thinking, how can I be a good ancestor?” he says.

“An understanding of what has happened in the past is helpful for anticipating or interpreting what’s happening in the present and what might happen in the future,” says Cerf. There are “all kinds of scenarios where the absence of knowledge of the past is a debilitating weakness for a society.”

“If we don’t remember, we can’t think, and the way that society remembers is by writing things down and putting them in libraries,” agrees Kahle. Without such repositories, he says, “people will be confused as to what’s true and not true.”

Kahle started the Internet Archive as a way to make sure all knowledge is free for anyone, but he feels the balance of power has tilted away from libraries and toward corporations. And that is likely to be a problem for keeping things accessible in the long term.

“If it’s left up to the corporations, it’s all gone,” he says. “Not only are we talking about classic published works—like your magazine, or books—but we’re talking about Facebook pages, Twitter pages, your personal blogs. All of those in general are on corporate platforms now. And those will all disappear.”

Losing our long-term digital archives has real implications for how society runs, says Harvard’s Cushman, who points out that our legal decisions and paperwork are largely stored digitally. Without a permanent, unalterable record, we can no longer rely on past judgments to inform the present. His team has created ways to let courts and law journals put copies of web pages on file at the Harvard Law Library, where they are stored indefinitely as a record of legal precedent. It’s also creating tools to let people interact with these archives by scrolling through historical versions of a site, or by using a custom GPT to interact with collections.

Many other groups are working on similar solutions. The US Library of Congress has suggested standards for storing video, audio, and web files so they are accessible for future generations. It urges archivists to think about issues such as whether the data includes instructions on how to access it, or how widely adopted the format has been (the idea being that a more prevalent one is less likely to become obsolete quickly).

But ultimately, digital archives are harder to keep than physical archives, says Cushman. “If you run out of budget and leave books in a quiet, dark room for 10 years, they’re happy,” he says. “If you fail to pay your AWS bill for a month, your files are gone forever.”

Storage for impossible time scales

Even the physical way we store digital data is impermanent. Most long-term storage in data centers—for use in disaster recovery, among other applications—is on magnetic hard drives or tape. Hard drives wear out after a few years. Tape is a little better, but it still doesn’t get you much beyond a decade or so of storage use before it begins to fail.

Companies make new backups all the time, so this is less of a problem for the short-to-medium term. But when you want to store important cultural, legal, or historical information for the ages, you need to think differently. You need something that can store huge amounts of data but can also withstand the test of time and doesn’t need constant care.

DNA has often been touted as a long-term storage option. It can store astonishing amounts of information and is incredibly long-lasting. Pieces of bone contain readable DNA from many hundreds of thousands of years ago. But encoding information in DNA is currently expensive and slow, and specialized equipment is required to “read” the information back later. That makes it impractical as a serious long-term backup for our world’s knowledge, at least for now.

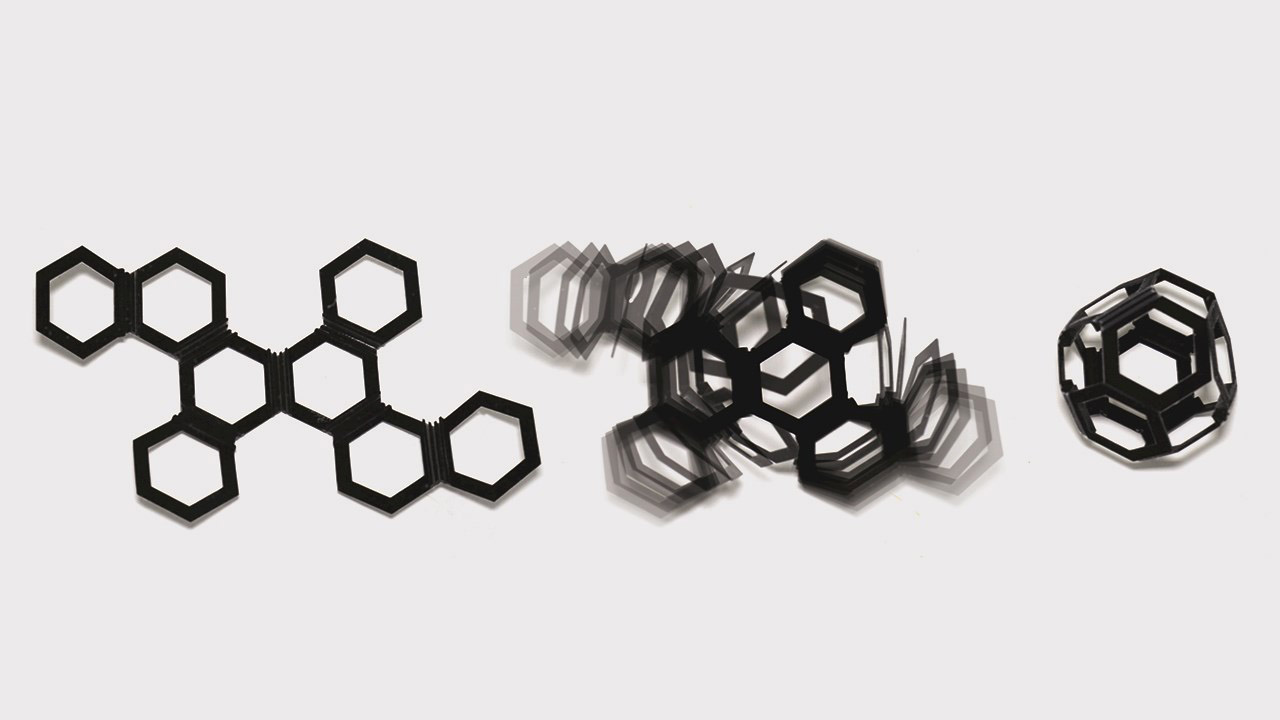

Luckily, there are already a handful of compelling alternatives. One of the most advanced ideas is Project Silica, currently under development at Microsoft Research in Cambridge, UK, where Richard Black and his team are creating a new form of long-term storage on glass squares that can last hundreds or even thousands of years.

Each one is created using a precise, powerful laser, which writes nanoscale deformations into the glass beneath the surface that can encode bits of information. These tiny imperfections are layered up on top of one another in the glass and are then read using a powerful microscope that can detect the way light is refracted and polarized. Machine learning is used to decode the bits, and each square has enough training data to let future historians retrain a model from scratch if required, says Black.

When I hold one of the Silica squares in my hand, it feels pleasingly sci-fi, as if I’ve just pulled it out to shut down HAL in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The encoded data is visible as a faint blue where the light hits the imperfections and scatters. A video shared by Microsoft shows these squares being microwaved, boiled, baked in an oven, and zapped with a high-powered magnet, all with no apparent ill effects.

Black imagines Silica being used to store long-term scientific archives, such as medical information or weather data, over decades. Crucially, the technology can create archives that can be air-gapped (cut off from the internet) and need no power or special care. They can just be locked away in a silo and should work fine and be readable centuries from now. “Humanity has never stopped building microscopes,” says Black. In 2019 Warner Bros. archived some of its back catalogue on Silica glass, including the 1978 classic Superman.

Black’s team has also designed a library storage system for Silica. Shelves packed with thousands of the glass squares line a small room at the Cambridge office. Handbag-size robots attached to the shelves whiz along them and occasionally stop, unclip themselves from one shelf, and clamber up or down to another before shooting off again down the line. When they reach a specific spot, they stop and pluck one of the squares, no bigger than a CD, from the shelf. Its contents are read and the robot zips back into position.

Meanwhile, deep in the vaults of an abandoned mine in Svalbard, Norway, GitHub is storing some of history’s most important software (including the source code for Linux, Android, and Python) on special film its creators claim can last for more than 500 years. The film, made by the firm Piql, is coated in microscopic silver halide crystals that permanently darken when exposed to light. A high-powered light source is used to create dark pixels just six micrometers across, which encode binary data. A scanner then reads the data back. Instructions for how to access the information are written in English on each roll, in case there is no longer anyone around to explain how it works.

In addition to GitHub’s collection, the storage facility, known as the Arctic World Archive, also includes data supplied by the Vatican and the European Space Agency, as well as various artworks and images from governments and institutions around the world. Yale University, for example, has stored a collection of software, including Microsoft Office and Adobe, as Piql data. Just a few hundred meters down the road you find the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a storage facility preserving a selection of the world’s biodiversity for future generations. Data about what each seed container holds is also stored on Piql film.

Making sure this information is stored in formats that can be decoded hundreds of years from now will be crucial. As Cushman points out, we still argue over the proper way to play Charlie Chaplin films because the intended playback speed was never recorded. “When researchers are trying to access these materials decades in the future, how expensive will it be to build tools to display them, and what will be the chances that we get it wrong?” he asks.

Ultimately, the motivation for all these projects is the idea that they will act as humanity’s backup. A long-term medium that will withstand an apocalypse, an electromagnetic pulse from the sun, the end of civilization, and let us start again.

Something to let people know we were here.

Happy accidents

Sometime in the first century, a Roman woman called Claudia Severa was planning a big birthday party at a fort in northern England. She asked her servant to write out an invitation to one of her best friends on a wooden tablet and then signed it with a flourish.

Claudia could never have suspected that, almost 2,000 years on, the Vindolanda Tablets (of which her invitation is the most famous) would be used to give us a unique insight into the daily lives of Romans in England at that time.

That’s always the way. Throughout history, the oddest, most random things survived to act as a guide for historians. The same will go for us. Despite the efforts of archivists, librarians, and storage researchers, it’s impossible to know for sure what data will still be accessible when we’re long gone. And we might be surprised at what they find interesting when they come across it. Which batch of archived emails or TikToks will be the key to unlocking our era for future historians and anthropologists? And what will they think of us?

Historians foraging through our digital detritus may be left with a series of unanswerable questions, and they’ll just have to make best guesses.

Throughout history, the oddest, most random things survived to act as a guide for historians. The same will go for us.

“You’d need to ask about who had digital technology,” says Bell. “And how did they power it? And who got to make choices about it? And how was it stored and circulated? And who saw it?”

We don’t know what will still be running 20, 50, or 100 years from now. Perhaps Google Photos’ cloud storage will have been abandoned, a giant garbage pile of old hard drives buried in the ground. Or maybe, with luck, one of the spiritual heirs to Scott’s archivists will have saved it before it went down.

Maybe someone downloaded it onto some sort of glass disc and stashed it in a vault somewhere.

Maybe some future anthropologist will one day find it, dust it off, and find that it’s still readable.

Maybe they’ll select a file at random, spin up some sort of software emulator, and find a billion photos from 2013.

And see a chubby, happy girl sitting in the grass.

Deep Dive

Culture

Happy birthday, baby! What the future holds for those born today

An intelligent digital agent could be a companion for life—and other predictions for the next 125 years.

This designer creates magic from everyday materials

Skylar Tibbits coined the term “4-D printing” – then immediately moved on to his next blue-sky idea.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.