Andrew Ng’s new model lets you play around with solar geoengineering to see what would happen

The climate emulator invites you to explore the controversial climate intervention. I gave it a whirl.

AI pioneer Andrew Ng has released a simple online tool that allows anyone to tinker with the dials of a solar geoengineering model, exploring what might happen if nations attempt to counteract climate change by spraying reflective particles into the atmosphere.

The concept of solar geoengineering was born from the realization that the planet has cooled in the months following massive volcanic eruptions, including one that occurred in 1991, when Mt. Pinatubo blasted some 20 million tons of sulfur dioxide into the stratosphere. But critics fear that deliberately releasing such materials could harm certain regions of the world, discourage efforts to cut greenhouse-gas emissions, or spark conflicts between nations, among other counterproductive consequences.

The goal of Ng’s emulator, called Planet Parasol, is to invite more people to think about solar geoengineering, explore the potential trade-offs involved in such interventions, and use the results to discuss and debate our options for climate action. The tool, developed in partnership with researchers at Cornell, the University of California, San Diego, and other institutions, also highlights how AI could help advance our understanding of solar geoengineering.

The current version is bare-bones. It allows users to select different emissions scenarios and various quantities of particles that would be released each year, from 25% of a Pinatubo eruption to 125%.

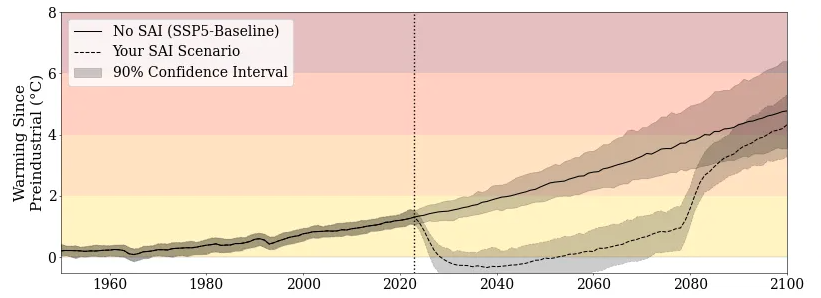

Planet Parasol then displays a pair of diverging lines that represent warming levels globally through 2100. One shows the steady rise in temperatures that would occur without solar geoengineering, and the other indicates how much warming could be reduced under your selected scenario. The model can also highlight regional temperature differences on heat maps.

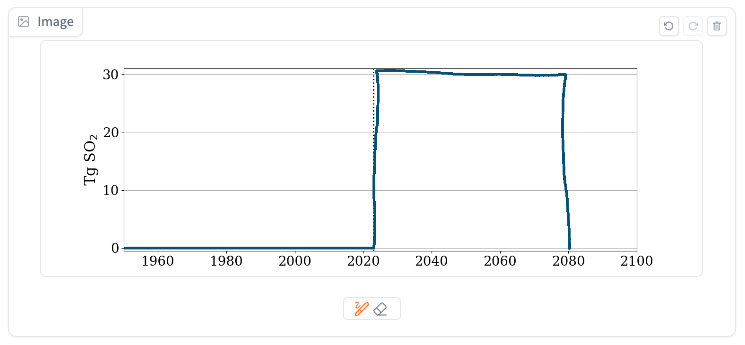

You can also scribble your own rising, falling, or squiggling line representing different levels of intervention across the decades to see what might happen as reflective aerosols are released.

I tried to simulate what’s known as the “termination shock” scenario, exploring how much temperatures would rise if, for some reason, the world had to suddenly halt or cut back on solar geoengineering after using it at high levels. The sudden surge of warming that could occur afterward is often cited as a risk of geoengineering. The model projects that global temperatures would quickly rise over the following years, though they might take several decades to fully rebound to the curve they would have been on if the nations in this simulation hadn’t conducted such an intervention in the first place.

To be clear, this is an exaggerated scenario, in which I maxed out the warming and the geoengineering. No one is proposing anything like this. I was playing around to see what would happen because, well, that’s what an emulator lets you do.

You can give it a try yourself here.

Emulators are effectively stripped-down climate models. They’re not as precise, since they don’t simulate as many of the planet’s complex, interconnected processes. But they don’t require nearly as much time and computing power to run.

International negotiators and policymakers often use climate emulators, like En-ROADS, to get a quick, rough sense of the impact that potential rules or commitments on greenhouse-gas emissions could have.

The Parasol team wanted to develop a similar tool specifically to allow people to evaluate the potential effects of various solar geoengineering scenarios, says Daniele Visioni, a climate scientist focused on solar geoengineering at Cornell, who contributed to Planet Parasol (as well as an earlier emulator).

Climate models are steadily becoming more powerful, simulating more Earth system processes at higher resolutions, and spitting out more and more information as they do. AI is well suited to help draw meaning and understanding from that data. It’s getting ever better at spotting patterns within huge data sets and predicting outcomes based on them.

Ng’s machine-learning group at Stanford has applied AI to a growing list of climate-related subjects. Among other projects, it has developed tools to identify sources of methane emissions, recognize the drivers of deforestation, and forecast the availability of solar energy. Ng also helps oversee the AI for Climate Change bootcamp at the university.

But he says he’s been spending more and more of his time exploring the potential of solar geoengineering (sometimes referred to as solar radiation management, or SRM), given the threat of climate change and the role that AI can play in advancing the research field.

There are “many things one can do—and that society broadly should work on—to help address climate change, first and foremost decarbonization,” he wrote in an email. “And SRM is where I’m focusing most of my climate-related efforts right now, given that this is one of the places where engineers and researchers can make a big difference (in addition to decarbonization).”

In a 2022 piece, Ng noted that AI could play several important roles in geoengineering research, including “autonomously piloting high-altitude drones” that would disperse reflective particles, modeling effects of geoengineering across specific regions, and optimizing techniques.

Planet Parasol itself is built on top of another climate emulator, developed by researchers at the University of Leeds and the University of Oxford, that relies on the rules of physics to project global average temperatures under various scenarios. Ng’s team then harnessed machine learning to estimate the local cooling effects that could result from varying levels of solar geoengineering, says Jeremy Irvin, a grad student in his research group at Stanford.

One of the clearest limits of the current version of the tool, however, is that the results look dazzling. In the scenarios I tested, solar geoengineering cleanly cuts off the predicted rise in temperatures over the coming decades, which it may well do.

That might lead the casual user of such a tool to conclude: Cool, let’s do it!

But even if solar geoengineering does help the world on average, it could still have negative effects, such as harming the protective ozone layer, disturbing regional rainfall patterns, undermining agriculture productivity, and changing the distribution of infectious diseases.

None of that is incorporated in the results as yet. Plus, a climate emulator isn’t equipped to address deeply complex societal concerns. For instance, does researching such possibilities ease pressure to address the root causes of climate change? Can a tool that works at the scale of the planet ever be managed in a globally equitable way? Planet Parasol won’t be able to answer either of those questions.

Holly Buck, an environmental social scientist at the University at Buffalo and author of After Geoengineering, questioned the broader value of such a tool along similar lines.

In focus groups that she has conducted on the topic of solar geoengineering, she’s found that people easily grok the concept that it can curb warming, even without seeing the results plotted out in a model.

“They want to hear about what can go wrong, the impact on precipitation and extreme weather, who will control it, what it means existentially to fail to deal with the root of the problem, and so on,” she said in an email. “So it is hard to imagine who would actually use this and how.”

Visioni explained that the group did make a point of highlighting major challenges and concerns at the top of the page. He added that they intend to improve the tool over time in ways that will provide a fuller sense of the uncertainties, trade-offs, and regional impacts.

“This is hard, and I struggled a lot with your same observation,” Visioni wrote in an email. “But at the same time … I came to the conclusion it’s worth putting something down and work[ing] to improve it with user feedback, rather than wait until we have the perfect, nuanced version.”

As to the value of the tool, Irvin added that seeing the temperature reduction laid out clearly can make a “stronger, lasting impression.”

“We are calling for more research to push the science forward about other areas of concern prior to potential implementation, and we hope the tool helps people understand the capabilities of SAI and support future research on it,” he said.

Deep Dive

Climate change and energy

This rare earth metal shows us the future of our planet’s resources

The story of neodymium reveals many of the challenges we’ll likely face across the supply chain in the coming century and beyond.

Want to understand the future of technology? Take a look at this one obscure metal.

Here’s what neodymium can tell us about the next century of material demand.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.